Systematic review databases are the primary sources of information in systematic reviews. They are the main component of the information sources in systematic reviews.

Typically, any systematic review aims to synthesize all the evidence available. Let’s say you’re doing a systematic review on the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy in treating depression among adolescents. You aim to identify all studies investigating the effectiveness of the intervention in treating the condition among the target population.

However, it is often impossible to retrieve all studies available on that topic. Consequently, you must rely on probability theory to select as many studies as possible whose findings are representative of the collective findings of all the studies on that topic. You’ve probably heard about selection bias in randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Researchers usually mitigate it by randomizing participant allocation. Nevertheless, randomization is not possible in systematic reviews. Therefore, you must implement a sound approach to minimize selection bias as much as possible.

Selection bias in systematic reviews occurs when the findings of the selected studies do not represent the findings of all studies available on that topic. You can minimize this bias by selecting as many databases as possible. In fact, the main difference between systematic reviews and narrative reviews is the manner in which selection bias is addressed. A review qualifies to be a systematic review if it has addressed selection bias to the greatest extent possible. Otherwise, it will qualify to be a narrative review if the chances of selection bias are high.

With that in mind, the next question to ask yourself is, how many databases do you need for a systematic review? In their exploratory study on this issue, Bramer and colleagues considered various factors when performing optimal database searches. They include balancing the laborious and time-consuming nature of performing database searches and minimizing selection bias as much as possible. In other words, you’re not going to search all databases and other sources of information available for your topic and subject. It is practically impossible because each database has its intricacies, such as unique search syntaxes.

Based on the logic described above, Bramer and colleagues concluded that a combination of the following databases can yield optimal results: EMBASE, MEDLINE, Web of Science Core Collection, and Google Scholar (Table 1). They particularly found that searching databases can yield approximately 95% of all studies available on that topic, which minimizes selection bias significantly. They additionally recommended that searching other databases like CINHAL and PsycINFO can provide unique references, especially in systematic reviews where the topic is related to the database coverage.

However, it is important to note that the databases recommended by Bramer (and colleagues) are solely for healthcare sciences. The systematic review methodology is more developed in healthcare sciences than in other subjects or disciplines. Therefore, there is more empirical evidence available supporting methodological recommendations. In other subjects where the systematic review methodology is gaining prominence, such as business, finance, and management, there are fewer empirically supported guidelines. For developing this resource, we relied on recommendations from experts in each subject.

Table 1 below provides a comprehensive overview of systematic review databases in health sciences.

Table 1: Description of systematic review databases commonly used in healthcare sciences. This table describes each database and defines its scope and number of indexed journals. This overview will inform you in your choice of databases in subjects like nursing, medicine, pharmacy, social work, etc. However, always ensure to back up your choice of databases with a peer-reviewed resource.

| Database | Description | Scope | No. of Journals Indexed |

|---|---|---|---|

EMBASE |

One of the largest systematic review databases online because it indexes second tier European and Asian journals not covered by MEDLINE. According to Bramer and colleagues, you must search EMBASE to consider a systematic review credible and comprehensive and with minimal selection bias. Though some argue that Scopus is the largest online bibliographic database because it covers all the EMBASE citations and beyond. Therefore, we recommend that Scopus be an alternative to EMBASE. The Emtree indexing in EMBASE covers a wider range of medical terms than MEDLINE’s medical subject headings (MeSH terms). | The database covers a wide range of subjects in all healthcare sciences, such as pediatrics, psychiatry, midwifery, radiology, genetics, general biology, palliative care, and nursing practice. For more information about EMBASE coverage, click here. | 3,000 journals unique to EMBASE and 8,200 published journals, including MEDLINE citations. (2023) |

Scopus |

As per Bramer and colleagues’ exploratory study, Scopus does not mandatorily yield optimal results if you have already searched databases like EMBASE, MEDLINE, and Web of Science Core Collection. It is the largest multidisciplinary database in terms of the coverage of academic journals. In our experience, Scopus is a better alternative to EMBASE because of its wide coverage. | The database covers content in more than 240 disciplines, including all healthcare sciences, humanities, and computer science. Literary, literature on any discipline can be accessed via Scopus. For more information about their coverage, visit this link. | 26,591 peer-reviewed academic journals (2023) |

MEDLINE |

The US’ National Library of Medicine (NLM)’s MEDLINE is one of the most extensive systematic review databases in healthcare sciences. Results from MEDLINE in Ovid and PubMed are often combined into a single database called MEDLINE. MEDLINE is the primary component of PubMed, but covers beyond. We recommend that if you have searched MEDLINE via PubMed, there is no need to perform another search via Ovid, and the vice versa. The main distinction between MEDLINE and other databases is that articles are indexed with NLM Medical Subject Headings (MeSH). For more information about PubMed, visit here. | The databases focuses on journal articles in life sciences, concentrating on biomedicine. | 5,200 peer-reviewed journals worldwide (2023) |

Web of Science Core Collection |

Like Scopus, Web of Science Core Collection is also a multidisciplinary database. Bramer and colleagues recommended the need for using at least one multidisciplinary database to increase search sensitivity. Thus, we also recommend Web of Science Core Collection as an alternative to Scopus. However, both can be searched in a systematic review. More information about Web of Science Core Collection can be accessed here. | 254 disciplines across the sciences, social sciences, arts, and humanities. | 21,000+ peer-reviewed journals; 300K+ conferences covered. |

Google Scholar |

Google Scholar is not an electronic database even though often used in systematic reviews in various disciplines. Instead, it is a search engine that indexes scholarly materials, including journal articles, books, book chapters, and grey literature. Examples of grey literature include governmental publications, organizational publications, and student theses and dissertations. Apart from optimizing the search strategy, another way of minimizing selection bias in systematic reviews is to also consider grey literature. Therefore, including Google Scholar in your systematic review can potentially minimize selection bias. | It indexes all scholarly materials crawlable on the Internet regardless of country of origin or discipline. | More than 100 million scholarly materials (2015) |

CINHAL |

Bramer and colleagues recommended the use of CINHAL as a subject-specific database to supplement EMBASE, MEDLINE, Web of Science Core Collection, and Google Scholar. CINHAL is subject-specific because it indexes journals in nursing and allied health sciences only. CINHAL subject headings closely follow the structure of NLM’s MeSH terms. | Nursing and allied health literature. | 1,314 peer-reviewed journals worldwide. (2023) |

PsycINFO |

American Psychological Association (APA)’s PsycINFO is also another subject-specific database that should be used if the systematic review’s topic is within behavioral sciences and mental health. Like EMBASE, MEDLINE, and CINHAL, PsycINFO also uses controlled vocabulary or index terms. For the records shared between PsycINFO and PubMed (about 30%), NLM’s MeSH terms are also transferred to PsycINFO’s records. However, PsycINFO has its unique controlled vocabulary used to index articles in their database. | It has recently expanded its scope beyond behavioral sciences and mental health to include business, law, education, sociology, social work, and political science. For more information about PsycINFO’s coverage, visit this link. | 2,400 peer-reviewed journals. (2023) |

In summary, systematic review databases in healthcare sciences can be categorized into three. First, there are multidisciplinary databases, namely Scopus and Web of Science Core Collection. We recommend using at least one of them in a systematic review to achieve optimal search sensitivity. Though using both of them can be more advantageous as they have different coverages regarding number of journals indexed. Second, subject-specific databases can be further categorized into small versus larger databases in terms of journals indexed. Larger databases are subject-specific (e.g., MEDLINE and EMBASE) and have more than 5,000 indexed journals. Smaller databases are subject-specific and have less than 5,000 indexed journals (e.g., CINHAL and PsycINFO). Finally, Google Scholar is a unique source of information. It is not categorized as an academic database. Instead, it is an academic search engine that indexes both scholarly materials and grey literature.

Overall, we recommend the use of at least one multidisciplinary database, two larger databases, at least one smaller database, and Google Scholar to achieve optimal search sensitivity. This recommendation is particularly extrapolated from the exploratory study conducted by Bramer and colleagues.

In whichever discipline, including healthcare sciences, it is always important to use multidisciplinary databases in your systematic review. These multidisciplinary databases are mainly Scopus and Web of Science Core Collection. However, although they are multidisciplinary, they do not cover all the available disciplines in academia. It is essential to confirm whether these databases cover your discipline.

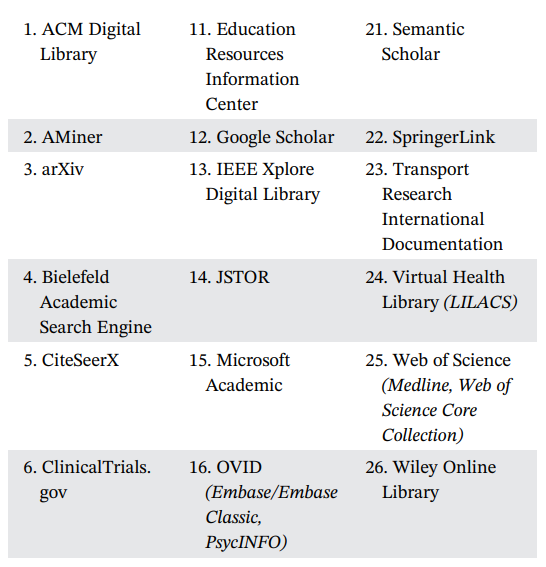

We also recommend using scholarly materials to identify academic databases commonly used in your discipline. For example, the infographic below was adopted from a scholarly paper investigating the precision of various academic databases and platforms for literature search. The authors of the paper did not specify which disciplines are more suitable for which databases. Instead, they grouped 28 databases commonly searched in systematic reviews in various disciplines. Because of the long list (the authors did not cover all available databases), we will leave this as a take away assignment to find out which databases are suitable for which disciplines. We have already covered some in Table 1 above. Focus on the remaining ones.

Ways you can access credible information about these databases is to visit their official websites. Here, they have provided crucial information, such as their discipline coverage, number of journals indexed, countries of focus, and the volume and type of records published.

In conclusion, choosing optimal databases for a systematic review is key to unbiased findings. Systematic reviews aim to synthesize all the literature available on a given topic. However, practically, it is impossible to identify all the available studies. The goal is to achieve a search sensitivity of at least 95%. This value can be increased even further if you use a combination of multidisciplinary and subject-specific large and small databases. Our team of experts can help you choose optimal databases for your systematic review, regardless of discipline or academic level.

Delivering a high-quality product at a reasonable price is not enough anymore.

That’s why we have developed 5 beneficial guarantees that will make your experience with our service enjoyable, easy, and safe.

You have to be 100% sure of the quality of your product to give a money-back guarantee. This describes us perfectly. Make sure that this guarantee is totally transparent.

Each paper is composed from scratch, according to your instructions. It is then checked by our plagiarism-detection software. There is no gap where plagiarism could squeeze in.

Thanks to our free revisions, there is no way for you to be unsatisfied. We will work on your paper until you are completely happy with the result.

Your email is safe, as we store it according to international data protection rules. Your bank details are secure, as we use only reliable payment systems.

By sending us your money, you buy the service we provide. Check out our terms and conditions if you prefer business talks to be laid out in official language.